By E. Sappir

Revising history is rightly viewed as a universal injustice. Cloaked under the noble guise of educational and literary advancement, books filled with historical distortions often wreak irreversible damage as they paint history in completely inaccurate colors.

As Jews, we have firsthand experience with ramifications of such activities. For decades, the Arab world continues to publish textbooks and maps with the State of Israel erased. Young, impressionable minds study history books that show Israel as a non-entity. In the early 19th century, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch wrote prolifically against Reformists who compiled heavy tomes with “a cavalier, superficial and untruthful treatment to documentary sources” (Collected Writings).

One could be forgiven for thinking that literary prejudice does not exist in the Orthodox community. The fundamental elements of hakoras hatov and truth are so firmly ingrained in the psyche that it precludes the motivation to redefine, alter and revise.

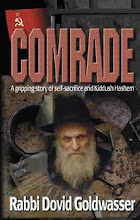

Yet a recent book does just that, albeit on a smaller scale. “Comrade” (Goldwasser, Targum/Feldheim) purports to be the honest translation of the memoirs compiled by a Hasidic shochet from the former Soviet Republic, but has become another cog in the growing machinery of Jewish revisionism. There is clear deception here. The translator—who had assisted Lifshitz in Russia—carefully manipulates the story to satisfy ulterior considerations.

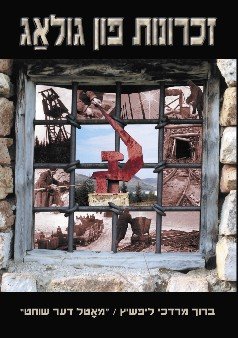

The hero’s family is aghast. “My grandfather thought his memoirs were being translated, not rewritten,” says one of his grandchildren. “The author was very friendly with my grandfather and earned his trust; now he is devastated. For example, my grandfather specifies that he recorded his memoirs based on directives of the Lubavitcher Rebbe; the author deleted that and claims he suggested and complied the biography himself. The original memoir was published in Yiddish—Zichronos fun Gulag—so non one needs to take anyone word for it, people can see the distortions for themselves. His book should be retracted.”

Lifshitz drew his strength from Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, a Jewish leader who would not be intimidated by the Soviets. Lifshitz’s studies in Chasidism, participation in Chasidic gatherings, and association with Schneersohn and his many followers are crucial elements in his gripping life story—yet they have almost all been carefully deleted. Aside from briefly mentioning a bracha of Rabbi Yosef Y. Schneersohn, the book is nearly “Chasidism-free.”

Erasing Israel from a map of the Middle East is inexcusable. Rehashing the role of George Washington in American history is wrong. Writing a book about the influential Mussar movement and removing references to Rabbi Yisrael Salanter does a great disservice to the greater Jewish community. Translating a memoir about the secret advancement of Yiddishkeit under the noses of the Soviets while intentionally distorting the incalculable contributions of Chasidism and Rabbi Yosef Y. Schneersohn is simply indefensible. The author —a community leader, rav, and noted lecturer—should know better.

1 comment:

Post a Comment